The relationship between media producers and audiences is “undergoing a significant transformation”, and thus entities such as fans, consumers, audiences, producers and corporations are individually in the process of being “restructured and reorganised” (Banks 2002, 190). Traditionally, there was hardly a relationship between media producers and audiences. Media provided audiences with content in a one-way approach, believing that most audiences were not interested in interacting with the media content, and would prefer to just sit back and watch (Jenkins 2006b, 59). Although there have always been fans, the extent of fandom in the past was not necessarily significant enough to influence media producers. Historically, networks and producers ignored fan bases in regard to media decisions, considering fans as unrepresentative of the general public (Jenkins 2006b, 76). Before the introduction of the Internet, fans communicated on a friendship basis, via telephone or face to face; or through fan mail and newsletters via postal service. However, as Jenkins (2002, 189) argues, if fandom was already established before the Internet, why is it that upgrading to a digital environment has so significantly affected the relationship between the fan community and media producers?

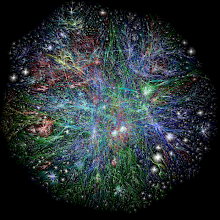

Jenkins (2006a, 21) describes modern fan cultures as "a revitalisation of the old folk culture process in response to the content of mass culture". Within the new digital environment of the Internet, fans no longer need to rely on the postal service or telephones. The Internet increases the speed and range of fandom, allowing audiences to interact and discuss episodes or movies immediately after viewing, or even during commercial breaks (Jenkins 2002, 190). Fandom generates audience interest and takes their involvement to a new level, providing a platform for viewers to inform each other of recent developments, allowing them to keep up-to-date constantly, even if they happen to miss an episode. For example, Lost-TV is an unofficial fansite for the TV series Lost, which includes the latest announcements and exclusives on the show, information, episode-by-episode synopses, transcripts, spoilers, pictures, an online forum and much more. Media producers have embraced this, ensuring that audience loyalty remains even if they are unable to religiously watch the program. In addition to this, fan networks provide producers with an insight into how audiences feel about the content of the program, suggestions and speculations that are being made, and any other discussions surrounding the program. As a result of this, many fans expect that producers will now “actively listen to, engage with and support” their opinions and ideas, building a collaborative relationship with them (Banks 2002, 195). As fandom becomes increasing popular, it is becoming more influential over producers, and providing them a greater insight into audience desires and expectations.

The growth of fandom has resulted in audiences and media producers no longer being separate entities. Many producers are themselves fans, participating actively in fan networks on the Internet (Banks 2002, 195). This also works the other way, as many audience members and fans are now becoming producers, either of original content, or by editing and reproducing current media. Examples of this include A Swarm of Angels, Fan Fiction and 365 Tomorrows. Over the past few decades, emerging technologies such as home computers, video cameras and VCRs have “granted viewers control over media flows, enabled activists to reshape and recirculate media content, lowered the costs of production and paved the way for new grassroots networks” (Jenkins 2002, 167), the most common and simple example of this being the development of YouTube. Pierre Levy (cited in Jenkins 2002, 164) comments on the future of media, “The distinctions between authors and readers, producers and spectators, creators and interpretations will blend to form a reading-writing continuum”. Many producers support this theory, and by using fan sites they have identified audiences’ need to interact with, interpret and reproduce content. Therefore, room for improvisation and participation is being incorporated into many new media franchises, and television producers are becoming extremely knowledgeable about their fan communities, often responding and expressing their support through networked computing (Jenkins 2002, 164). In doing this, media producers have given audiences a degree of social control over media, allowing them the grounds to produce their own content. Thus the relationship between media producers and audiences has indeed changed, with the two entities meshing and overlapping responsibilities.

Personally, I feel that regardless of the extent of power or influence audiences have over media producers, in the end those with the final say will be those with the money - the media producers. Unfortunately, as much as people may try and think otherwise, we are living in a material world and money tends to equal power. Even fans fear that the role of media producers is still too controlling - Jenkins (2006a, 20) points out that American Idol fans "fear that their participation is marginal and that producers still play too active a role in shaping the outcome of the competition". In terms of professional media productions, which ultimately aim to make money, producers will ensure that regardless of whether audiences are involved or not, the final product will be whatever they believe will be most successful... and make the most money. Produsage, user-generated content and fandom have all provided audiences with much more power than they ever had traditionally, however I believe that ultimately, the real power will always lie with media producers (and their money).

For more info on fandom check out:

- Online Fandom -Nancy Baym's blog on fan communication and online social life

- Random Fandom - a podcast hosted by Joanna, sharing her thoughts and opinions on fandom including music, pop culture, movies, etc

- Fan Forum - as it suggests, an online fan forum allowing fans to communicate and share their thoughts on their fandom

References

Banks, J. 2002. Gamers as Co-creators: Enlisting the Virtual Audience – A Report From the Net Face. In Mobilising the Audience, eds. M. Balnaves, T. O’Reagan, and J. Sternberg, 188-212. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Jenkins, H. 2006a. Introduction: Worship at the Altar of Convergence. In Convergence Culture: When New and Old Media Collide, ed. H. Jenkins, 1-24. New York: New York University Press.

Jenkins, H. 2006b. Buying into American Idol: How We Are Being Sold on Reality Television. In Convergence Culture: When New and Old Media Collide, ed. H. Jenkins, 59-92. New York: New York University Press.

Jenkins, H. 2002. Interactive Audiences? In The New Media Book, ed. D Harries, 157-170. London: BFO Publishing.